Behold, I emerge, bloodied but unbowed, having at last vanquished my foe. January is always a grim month in the world of higher education but this year it really took the biscuit. It is, however, over! Please enjoy this actual footage of me submitting the last of my marked assignments on Monday evening.

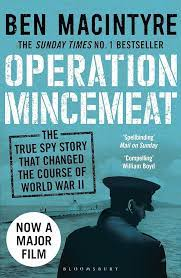

I have now finished most of the other assorted January tasks, so I return at last with a review of the only book I finished over the past month (and that before I even returned to work after Christmas). Operation Mincemeat, by Ben Macintyre, is a narrative nonfiction account of – as the name suggests – Operation Mincemeat. This was a deception operation carried out by British intelligence in the run up to Operation Overlord, designed to make the Nazis think that the landing point would be Sardinia rather than Sicily. In brief (and this is all I really knew before reading the book), a dead man was got up to look like a military attaché and “drowned” off the coast of Spain, where he would likely get passed to the Germans by fascist sympathisers – along with the case of top secret papers chained to his wrist, all containing invaluable hints about the starting point of the Allied invasion, and every one of them a fake.

Much of the story features Ewen Montagu, a highly aristocratic British lawyer, related to various Secretaries of State for India and other bigwigs. In peacetime, he had been very successful – happily married, wealthy, living a life that he later called “a continuous happy time… we were lucky in every way”. When war broke out, he became an intelligence officer, and became senior in the various deception operations that were carried out. While the very origins of Operation Mincemeat were not Montagu’s idea, he became the driving force of the operation. It does have a rather lawyerly quality, both in the way it was originally conceived, and in Macintyre’s reconstruction – close attention to the creation of documents, every i dotted and every t crossed.

Because of Montagu’s forceful personality and obsessive attention to detail in the creation of “Bill Martin” as a person, he really becomes the central character of the story. How much of that is because he was the only individual involved who was willing to tell the story in postwar Britain is anyone’s guess. It’s perhaps understandable that any story that got told in the immediate aftermath would reflect Montagu’s (undeniably high) opinion of himself. (In fact, several times as I’ve been writing this review, I’ve typed “Montagu” when I meant “Macintyre” – which I think reflects the extent to which Montagu has clearly been the biggest influence to date on how the story is told and understood). It was personal for him, though, as well as professional: Montagu was Jewish, and when he learnt that Hitler had himself been taken in by Operation Mincemeat, he said: “Joy of joys to anyone, and in particular a Jew, the satisfaction of knowing that they had directly and specifically fooled that monster”. It is immensely satisfying for the reader too.

Montagu is far from the only notable character in the book. It has all the key bits of a spy story, really: young women in swimsuits, creepy coroners, submariners, fifth columnists, heroic WWI flying aces, an intermittently intoxicated Winston Churchill… In truth, it’s difficult to sum the book up. That’s partly because (despite the fact that the reader knows going in that Operation Mincemeat achieved its aim) there are a surprising number of twists and turns, and I think this is the type of story it would be very easy to spoil. More than that, though, it’s because – like so many real-life stories – it is much weirder than a novel. I mean, if someone turned this into a publisher as a fictional thriller, they would be laughed out of the room. In fact, a number of detective novelists and thriller writers were involved in this story, one way or another – including Ian Fleming – and so it’s unsurprising that this reads so much like a postwar spy story. After all, this was part of the mix of events on which those writers were drawing when they sat down to write.

That’s not the only way Macintyre gave himself a very difficult job when he sat down to write this, either. It would be a challenge for any writer to tell this story well. It is undeniably a ridiculous, hilarious, Dad’s Army-esque cracking jape; yet, at the same time, it really happened, countless lives were dependent on it going well, and it happened alongside incredibly bleak events. To tell it as pure adventure story would be fine if it were a novel, but not the right tone for non-fiction. Macintyre manages to keep a light hand with the absurd elements (of which there are so, so many), while also setting it well in a context that is much less fun. For example, the body commandeered for the operation – by sheer virtue of being a body that nobody would miss – does not belong to someone who has had a happy life. Macintyre doesn’t shy away from this, and – while he wisely stays away from moral pontificating – I think he does his best to treat Glyndwr Michael (who was to become Bill Martin in death) with the respect and dignity that such an end inevitably deprived him of. Macintyre has to balance these two different tones throughout, creating a single writing voice, and he does a great job.

I do one or two grumbles. It fascinates me that many (not all) secular writers seem incapable of accepting that people act in accordance with their religious beliefs because they believe them. Macintyre tells the story of Alexis Baron von Roenne, a high-ranking Nazi who had a kind of Road to Damascus moment, came to deeply regret and repent his involvement with the regime, and spent the rest of his life working from within to undermine it. When he was eventually caught and subjected to a show trial, he gave as his defence that Nazi race laws were incompatible with Christianity – as indeed many other devout Christians did before they were executed in Germany in this period, as indeed is often the case when you start unpicking why people were involved in anti-Nazi activism and resistance across the whole of occupied Europe. He wrote to his wife the night before he was hanged, reassuring her that he knew he had done the right thing and that he went to his grave confident of his salvation. Macintyre tells us all this – and then says “it’s impossible to know why he behaved as he did”. No, it’s not. You just told us why he behaved as he did! You don’t have to personally believe that von Roenne was doing the will of God when he undermined the Nazi war effort to believe that he believed he was, and acted accordingly. Anyway. This is hardly a problem limited to Macintyre, but it did irritate me – particularly since he rarely applies this level of scepticism to his other primary sources.

Macintyre definitely writes as a journalist, not an historian. I listened to an interview with him where he says everything in his books is true and verifiable – the example he gave is that he won’t say it was a sunny afternoon unless someone somewhere has written down that it was sunny, and his sources are all extensively listed at the end – but there’s no indication that (to follow his analogy) he actually checks this against the day’s weather reports. The ins and outs of the escapade itself are documented and he has references to all the records, including in some cases photos. The story is clearly true in essentials, but some of the anecdotes he adds in for colour seem to be based on individual memory recounted after the fact. He rarely weighs facts or cross-checks his information – or if he does, that’s not visible in his storytelling.

Don’t go into this expecting that what you read will have been either triple-checked or caveated, then, as would (hopefully) be the case in work by an academic historian – but do go into it expecting to read a brilliant account of a weird, fascinating moment in history, told with great flair. Really, if you are at all interested in the history of espionage or WWII, this is an absolutely cracking read. I can’t recommend it highly enough!

Ben MacIntyre is definitely having a moment and has a few successful books now. I think your point about him being a journalist and not a historian is a good one.

He’s a great storyteller and I’ll definitely be picking up more of his work (and I’m going to see the stage musical based on this book next week, which I am *so* excited about)! I think some historians here have been a bit sniffy about him, but honestly I don’t think he’s trying to be an historian, nor presenting himself as one. He’s very good at what he does – it just isn’t history.

What I’ve noticed about his work is that it seems to appeal to a lot of readers who maybe wouldn’t pick up a more historical book. He’s reaching a wider audience and I think that’s a good thing!

I tend to like investigative journaling more than history books. I like the way the writer inserts him or herself into the narrative, making modern connections or describing what it was like to find information in an unlikely place. Jon Krakauer is good at this. Lately, I’ve been drawn more to nonfiction than fiction. Every so often, I feel like I can’t read one more fiction novel that sounds like everything that came before it, whereas the weird stuff is in the notification, which, as you mentioned, can be even weirder than invented stories.

I feel the exact opposite about history and journalism! I can’t stand it when writers insert themselves into the narrative. Probably my dislike of (most) memoir is to blame, but I so much prefer writers to stay focused on the topic about which they are supposedly writing. I’m also reading much more nonfiction at the moment – I haven’t finished a novel yet this year, except one reread right at the start of January.

I think a good example is when Jon Krakauer wrote Into the Wild he connected the free-spirited young man he was writing about with his previous book, Into Thin Air, which was about Krakauer’s own free-spirited adventure during which he almost died. I suppose it’s more about the author interjecting connections between stories and less about it being the author’s own personal story. To be fair, that’s how my brain works: I learn one thing and immediately go into a spiral connecting it to other things, which is how I remember new information.

I got my fill of British WWII adventure and spy stories in my teen years (fifteen or twenty years after the War) when they were everywhere, and now I positively avoid them.

Hmm, I didn’t get on with this one which was odd since I’ve enjoyed books of his before. It may have been while I was slumping, as I have quite a lot over the last couple of years, so inspired by your enthusiasm I shall resurrect it on my Kindle and try it again sometime in the future!

I’ve had the opposite experience – this is still the only book I’ve managed to finish this year (except a reread of an old favourite), so it is the only thing saving me from the worst reading slump I’ve had in years! (I have very nearly finished a second one, so I’m hoping the slump will be over soon).

Aargh! Read some Christie, quick! 😉